On Palestine

Mariam Ibrahim (Network Team)

This summer, after two decades, I finally made the trip back to Palestine to visit my extended family, to connect with the land, and renew my understanding of what life is like on the ground for the millions of Palestinians who continue to live under Israel’s unjust and illegal occupation.

As a child and later into my teens, visits to the West Bank, where the majority of my family live in Palestine, were common. Our trips usually meant a flight across the Atlantic, landing in Jordan where we would visit with a few aunts and uncles before making the often exhausting journey across the border into the West Bank. It was never a simple trip, of course because it involved an encounter with Israeli border guards, but also because several of our trips took place during the first and second Intifadas, or Palestinian uprisings, which were marked with heavy Israeli violence designed to quell any form of Palestinian resistance.

I can’t say for certain why it took me 20 years to return to the homeland, but the last time I visited was the summer before I entered university. So when my mother called me from Canada to let me know she was planning a summer trip to Palestine with my niece, who had never been but had spent the better part of a year asking to go, I took it as a sign that it was my chance to visit too.

The last time I had been was in 2003, which was during the second Intifada. It was common to see Israeli soldiers in their jeeps and tanks on the streets, and stories of young Palestinians killed by occupation soldiers were common. I attended funerals and protests, I got stopped at checkpoints where I saw kids as young as 10 being detained, and took wild routes through groves and over hills to get to cities like Nablus and TulKarem, because of arbitrary road closures and blockades.

While Palestinians in communities across the West Bank continue to resist the occupation in small and big ways, through direct action and through international activism like the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaign, the intensity that comes with an Intifada wasn’t there during this visit. That’s not to say that the threat of soldier and settler violence isn’t real and always present; during my time in the West Bank I heard many stories of young men who were killed or kidnapped, and settler attacks on Palestinians. But this time, for me, things looked and felt a lot different. I guess 20 years will do that.

What I first noticed was how much the landscape had changed. I barely recognized my surroundings as our taxi van drove us along the once familiar roads to my family’s village of Jayyous. Along the way, we passed dozens of Israeli settlements, illegal under international law, each one with their own Israeli checkpoint at the entrance to keep out Palestinians and provide dedicated protection services to inhabitants. Many of these settlements were continuing to expand, with active construction sites building along land that once belonged to Palestinian villages and towns. And the number of settlements is expected to continue to grow, fuelled by Israeli government policy to expedite their creation. The roads between the settlements were frequented by Israeli only bus services, and dotted with massive billboards with Hebrew advertisements encouraging their Israeli audiences to join one of these illegal communities. If I hadn’t known better, I wouldn’t believe that I was in what was effectively Palestinian territory.

When you ask people who are familiar with the question of Palestine how the issue should be solved, the opinions vary wildly. It’s a polarizing question, to be sure, but for me it has never been a complicated one. At its foundation, it is a question of colonialism. It is an example of indigenous inhabitants of the land who were forced out and not allowed to return; efforts of ethnic cleansing to rid the land of as many of its remaining inhabitants as possible, and an occupation designed to oppress and subjugate the rest. It is also an example of two tiers of treatment — modern day apartheid — in which Palestinians live under a very different system than their Israeli counterparts, including those Palestinians who carry Israeli citizenship.

For all of these reasons, I have always been a proponent of the one-state solution. To me, all people who live within a territory should have equal status: the same rights, the same vote, and the same freedoms. Today, many people continue to cling to an idea that the question of Palestine could be solved with a two-state solution. I’ve always viewed this as a morally bankrupt idea that ignores the rights of Palestinians who have the right to return to their homes in Yaffa and Akka and Haifa, cities that would all be claimed by an Israeli state. It’s also impossible for another reason, one I have always understood intellectually, but came to appreciate with my own eyes during my recent visit: the facts of the ground have changed so drastically, after decades of effort by successive Israeli governments that have allowed and encouraged illegal settlements to proliferate across the West Bank. It is hard to imagine what a Palestinian state would even look like today; a series of communities, many of which are cut off from each other and the land and water they need for their livelihoods because of Jewish-only settlements. It would mean the formal international acceptance of the oppression, injustice and apartheid that built it.

This is the reality that exists on the ground in the West Bank today. And yet, despite the unabated land theft, settlement expansion, and ongoing military occupation they have to contend with every day, Palestinians find joy in their lives every day. My two weeks in the West Bank were some of the most joyous I’ve had in a long time. The generosity, the laughter, the time spent in the fruit groves, in the old markets haggling with sellers and indulging in slices of kanafeh, the late night barbecues and family gatherings as the hot mint tea and extra strong coffee flowed between the stories and memories. Despite all the reasons for despair, we experienced joy on the land each day.

To quote the Palestinian activist and poet Rafeef Ziadah: “We teach life, sir. We Palestinians teach life after they have occupied the last sky.

“We teach life after they have built their settlements and apartheid walls, after the last skies.

“We teach life, sir.”

Below are some photos I took during my travels:

The view from my family village of Jayyous, which is kilometres away from the Green Line. In the distance you can see the highrises of an Israeli city.

A view of the Israeli apartheid wall from Jayyous. In some parts, this wall is an eight-metre high concrete barrier, but in Jayyous it is an electrified fence with a military patrol road. Many Jayyous families had their farm land confiscated for its construction.

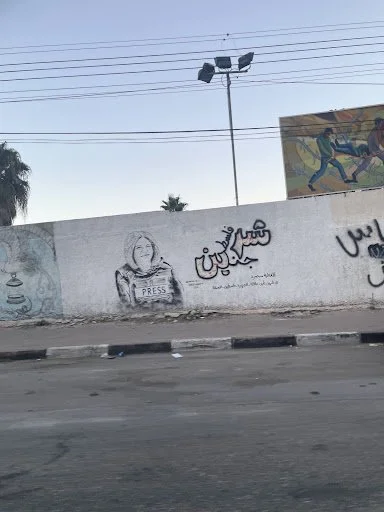

Graffiti in Nablus honouring Shireen AbuAkleh, the prominent Palestinian-American Al Jazeera journalist who was murdered by Israeli soldiers while reporting from the Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank.

A wall in the old city of Nablus honouring Palestinian resistance fighters killed by the Israeli military.

The illegal Israeli hilltop settlement of Zufim, near Jayyous, which is continuing its expansion with active construction efforts.